Rural Queer Spaces

“You’re born naked and the rest is drag” –RuPaul Charles, drag queen

Almost a mile from Roanoke’s downtown, a nondescript metal building sits across from a limousine garage on Salem Avenue. At first glance, it appears empty. The only indication that the building is not vacant is the see-through plastic sign that reads “The Park.”

Drag refers to the wearing of clothing of the opposite sex for entertainment purposes. There are different subgenres of drag that include male illusionists, who dress up as men for entertainment, and draq queens, who impersonate women for entertainment.

“There are no boundaries, no limits, no anything really,” said Eden Parque-Divine, a drag queen who often performs at The Park. “It is all about what you want to dedicate yourself as physically portraying and accomplish as your persona.”

There are misconceptions about drag—the performer must be gay, has to wear a dress, and has to be a man dressed as a woman. But performers see drag is an art form. Enya Salad, a 17-year veteran on the Roanoke drag circuit, said straight men with families have won the title of Mr. Gay Roanoke, and straight women have won other local pageants.

Within the drag community, families are formed to provide guidance and share information about performance. Anton Black, 43, is a male illusionist and a member of the Black-Haze drag family, which is comprised of male illusionists, femme fatales and most forms of drag in between.

Black almost didn’t find this outlet of expression. He was a self-described “shut-in” for 13 years because of agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder in which a person fears places or situations that might cause panic. With agoraphobia, a person might fear open or enclosed spaces, or being in a crowd. Black only left the house for his doctors’ appointments.

“[Staying in the house] became very comfortable for me,” he said.

His journey to drag began at Pride in the Park in 2012, Roanoke’s celebration of LGBT people. His wife, Maggie, convinced him to go with her and their kids to the annual event in Elmwood Park.

They ended up at The Park on a date for the first time in years.

Anton Black and his wife Maggie at The Park's Sunday drag brunch.

“There was this incredible sense of community,” he said. “Everybody was just very sweet and very nice to each other. It was extremely welcoming. So that night was just really magical in my mind.”

Black said he usually hates interacting with people. But he and his wife started frequenting The Park. It became their safe haven.

Four years ago, a cancer benefit launched his drag career. He almost didn’t perform, even though he was supposed to go on stage with his daughter Cory. Backstage, it was packed with close to 30 performers. Out in the bar, patrons surrounded the stage.

The scene triggered his agoraphobia. But his daughter convinced Black to perform by reminding him that it was for a good cause. He then began competing in Roanoke’s drag circuit. He won his first title during his first competition.

“I won right out of the gate,” he said.

Black said drag helped him get out of the “pit of despair” he had been in for years, and he realized that he didn’t have to live his life surrounded by the same four walls.

He said he still gets anxiety when he goes out in public, but said that he loves to perform.

“Which is really odd because I can’t go to Wal-Mart,” Black said.

Greg Rosenthal, a queer historian at Roanoke College, said competitive drag in Roanoke has been around for at least 40 years.

He said he was shocked when he went to The Park for the first time and saw how prominent drag performance was and how connected it is to the self-identity of the queer community.

“And I’ve got to imagine that has been a pathway for some trans people to discover themselves,” Rosenthal said.

Black was one of those people.

“A lot of people go, ‘It’s just drag, it’s just fake.’ To me, especially to me, it’s not just drag," Black said." It was a vehicle through which I grew as a person and found out a lot more about myself than I ever had before,” he said. “And that happens with a lot of these young people [as well].”

Black now sees himself as a mentor for young people trying to find themselves. He holds workshops at The Park on how to put on a beard, how to bind for the stage, among other things. Binding involves the compression of breasts for masculine appearance.

By putting on a beard and binding the chest, some transgender people experience confirmation of what they’ve been feeling all their lives—that they are trapped in the wrong body.

Black said he often received phone calls that lasted hours from young people who were struggling with what they realized while they were in drag.

“But the beard is huge,” he said. “You watch these young kids when they get sideburns and then they come down a little bit and you see their eyes go ‘Whoa,’ and you know. You just know.”

Black helped Brantley Meddings, 27, decipher his feelings and identity.

“I felt right looking at the person [in the mirror],” Meddings said. “I felt like who I was supposed to be.”

Nestled in the Bible Belt of the Appalachian Mountains, Roanoke is a stark contrast to its sister city Lynchburg, home to the late Jerry Falwell, the fundamentalist preacher and founder of Liberty University, a “Christian university for evangelical believers,” according to the school’s website.

Roanoke, in contrast, has always been a city of sin.

“Ever since the railroads came to Roanoke in the 1880s there have been brothels, there have been sex houses, there have been places for public sex,” said Greg Rosenthal, a professor of public history at Roanoke College. “So sometimes I talk about Roanoke as a city of sin.”

Rosenthal is one of the founders of the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project, a community-based history initiative committed to researching and telling the stories of LGBTQ+ individuals and organizations in the region.

Gregory Rosenthal's office at Roanoke College.

Rosenthal said more than 30 people have been interviewed and a public archive of LGBTQ+ history now resides in the downtown Roanoke Public Library.

He says Roanoke’s prostitution and red light district was in operation during the late 1800s.

“Roanoke has always been trying to crack down on vice and sin—sex, prostitution, that type of thing—but always allowing it at the same time,” Rosenthal said.

Roanoke’s former Mayor Joel Cutchin, who was in office from July 1902 to April 1912, was summoned before a grand jury for his failure to close down the brothels.

“And the grand jury investigations found out he was making money off of the brothels with the madams,” Rosenthal said. “He was dancing with prostitutes at 2 a.m. in the middle of the night. Our mayor! And this is 100 years ago.”

Roanoke’s culture of sex and vice didn’t escape Roanoke’s LGBT community. Rosenthal said that cruising in public parks, when people sought casual sex in the pre-technology age, was common in Roanoke as early as the 1960s. He said police efforts to stop gay men from cruising in the city’s public parks continued into the early 2000s.

Rosenthal’s research also yielded copies of the Virginia Gayzette and the Big Lick Gayzette, two gay papers that published in the 1970s. He said the newspapers provided their readers with advice on surviving as a gay person in Roanoke.

“This is pre-internet. This is the way gay people around Southern Virginia [were] communicating,” he said.

Rosenthal said he’s found “little snippets” in advertisements that he believes were placed by people who might identify as transgender today. These advertisements seemed to have been placed by people wanting to find others who dressed and expressed themselves as a different gender than what was assigned at birth, he said.

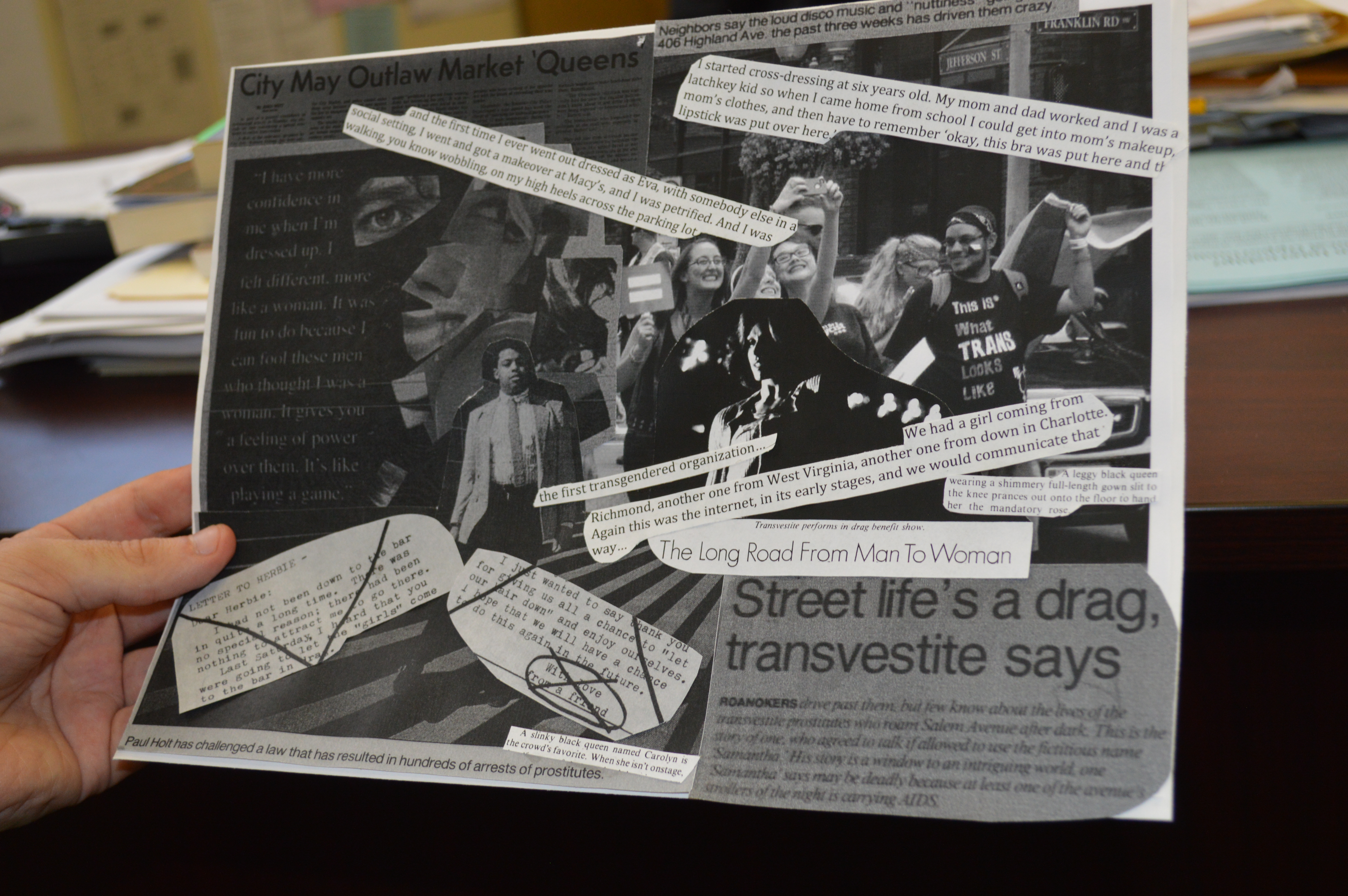

Gregory Rosenthal shows off clips from his archival work.

But Rosenthal said it’s hard to be sure because words like transgender weren’t used until the 1990s. He also said that gay newspapers wouldn’t be the best vehicle because “most cis-gay people could care less about that segment of society” at that time. Cis- refers to a person whose gender identity corresponds with their birth sex. For example, a cis-gay man would be a biological male who identifies as a man.

There is only one gay bar in Roanoke. But that isn’t how it used to be.

Rosenthal said the Virginia Gayzette used to publish a bar guide. In the 1978 guide, he said, there were “a hell of a lot more” gay bars than there are now. But these bars were not safe spaces for the entire LGBT community.

“The bar guide for every single bar has some line that says ‘proper gender please, no drag allowed,’” he said. “A warning basically, you will not be allowed inside if you are not presenting as your cis-gender identity.”

The bars were dominated by men who didn't want people of nonconforming genders to draw unwanted attention—from police or “straight punks,” who would cause trouble, Rosenthal said.

T.J. Tallie in his office at Washington and Lee University.

T.J. Tallie, a Washington and Lee University history professor who specializes in research into gender and sexuality, said the world is a “special safe space” for some people, and that it is important for marginalized groups to have spaces of their own.

“It’s about having a space to just breathe and not necessarily exist on the terms of the people who are the norm,” he said.

The Park is such a space for Roanoke’s trans community.

“You get out of the car, you get into the bar, you’re safe, you’re home, you’re accepted,” said Serenity, a self-described “chick with a dick.”

But Serenity said there are spaces in Roanoke that she cannot and should not go.

“You got to be careful these days,” she said. “There is a climate out there where people like myself, [there are] places we shouldn’t be and places we can be.”

Anton Black, who struggles with agoraphobia, said he’s vigilant about keeping track of where he is and who is around him. He says he won’t go anywhere he suspects he could be attacked.

Black said he often tells his friends and family, especially his trans female friends, to check out the places and people they will be around.

“I caution everybody to research,” he said. “Does it suck that we have to do that? Absolutely. But it’s better than you not returning home that night.”

Dolly Davis, a transgender advocate in Roanoke, said she has felt unsafe many times. Davis, who is hearing impaired, knows who is in the room at all times and knows who is behind her at all times.

“When you’re in a dark alley, I’ve got to worry about people identifying me as easy prey as a woman,” she said. “But if somebody knows that I am trans, then there is that added hatred.”

She said she has two options when she feels unsafe: show strength or show weakness. To show strength, she said, you hold your head high, throw your shoulders back and puff out your chest.

“You own that space. No one can take it away from you unless you let them. You have every right to be here as anybody else,” Davis said. “And if you act like you’re doing something wrong or that you’re ashamed of who you are, people—it’s like running from a dog—they will attack. If you stand up for yourself and put them on the defense … that is how I’ve learned is the best mechanism to help my self-preservation.”

Even though Davis is vigilant about her and her family’s safety, she doesn’t let her fear of confrontation control her.

“That’s what drives my advocacy, and that’s what drives a lot of other people’s advocacy,” she said. “Saying, ‘Damn it, I will not be controlled by these people with the fear. I will not be put in my place. I will not get out of society.’”